The Art Market, Cultural Protection & Provenance, Isabelle Imbert

- Feb 21, 2022

- 12 min read

Isabelle Imbert is an Islamic Arts historian, writer, speaker and podcast host. She got her PhD in Islamic Art History in the Sorbonne University in 2015 and has been working since as a freelance art advisor and scholar specialized on cultural interactions between Europe, India and Iran. Isabelle is also a member of the Institute of Art and Law, and has a particular interest for art trade legislations and practices.

We talk to Isabelle about the art market, the issue of provenance, collecting and transparency.

How did you develop a connection to Islamic art and what was your journey to becoming an Islamic Arts historian?

I owe my relationship with Islamic arts to curiosity, great mentors, and chance.

For as long as I can remember, I always knew I wanted to study art history, so after high school, I enrolled for an art history curriculum in the University of Toulouse le Mirail. I was asked to choose classes in addition to the main cursus, and one of them was “History of Byzantium and early Islam”. At 17 years old, I knew nothing about either of these fields, and I thought it would be interesting to learn more.

I remember how confused I was when Pr Philippe Senac, who was teaching the Islamic history class, started talking about pre-Islamic Mecca and the context in which the Prophet was brought, but also how amazed when, only a few weeks later, he showed us dinar from the early 8th century with an iconography mixing Byzantine and Sassanian imageries. This is when I decided to specialize in the field, I could not stay away from the world that was being offered to me.

Can you tell us more about the projects you have worked on?

In 2007, I moved to Paris to continue my studies in Islamic arts history under the supervision of Pr. Jean-Pierre Van Staevel and Pr. Eloise Brac de la Perriere. She first introduced me to the research topic of flower paintings produced in India and Iran between the 16th and the 18th centuries, which would become the topic of my doctoral dissertation. I spent five years working on it, but there is still work to be done on it, which I have planned for this year.

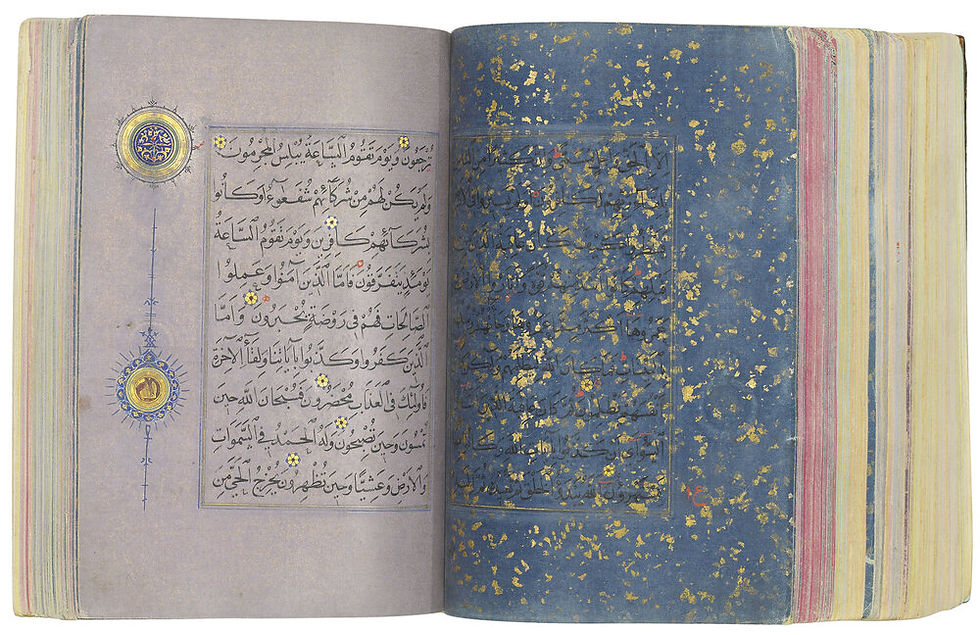

As a doctoral candidate, I can say I have done a lot, but I am particularly grateful to Pr. Brac de la Perriere for including me in two major research programmes that gave me such a solid base for later work. The first, from 2008 to 2010, was dedicated to the study of a 14th century Qur’an produced in Gwalior, India, and now kept in the Aga Khan Museum. It was a really great experience, during which I learned lots about academic project management. I was involved in the second one from 2010 until the obtention of my Ph.D. in 2015. Co-funded by Pr Brac de la Perriere and Dr Vernay-Nouri, now retired manuscript conservator in the Bibliotheque nationale de France, this project aimed to study of Arabic copies of Kalila wa Dimna fables, which have had such a massive impact on literature, from India to France. Because my field of expertise lies with Indian and Persian productions, it was really exciting to look at Arabic manuscripts, especially premodern ones that had been completely ignored by historiography until then. I also participated (humbly) in the preparation of an exhibition on the topic, held in the Institut du Monde Arabe in 2015, which gave me a new perspective on object conservation and diffusion of knowledge.

During that time, I also worked for Marie-Christine David, famous French expert, who passed away last year. It was one of my first contacts with the art market, and I still remember the day she received five pages produced for Antoine Polier, to be sold at Pierre Bergé. Antoine Polier lived in the 18th century and spent most of his life in India, during which he collected paintings and had beautiful albums produced by prestigious artists. Working on this valuation was such a privileged moment of my young years, that, years later, continued to open doors to new opportunities.

You currently work as a freelance researcher for art market specialists around Islamic Art. What does this entail?

I am in the somehow privileged position to operate between academia and the art market. This gives me a unique viewpoint, but also the independence to collaborate with art market professionals and auction houses, as well as private and public institutions.

I work with clients in need for in-depth research on objects they wish to acquire, sell, get valued, or just understand better. This usually includes an analysis of the technique, the production, the historical relevance of the artefact, but also of provenance when possible, and in some cases, an overview of potential litigation attached to its trade. It is a complex work that requires a lot of fine-tuning, as every object is different, and every client, context and needs differ as well. It is also very exciting because I have the privilege to work on beautiful pieces of art and of history, which should never be taken for granted.

How does Islamic art fit within the wider art market?

What we call “Islamic art”, though the term is highly debatable, is a very small part of the art market, it is very niche. Prices achieved by objects produced in the Islamic lands before the 20th century rarely compare to modern and contemporary productions that often fetch millions.

It is also a more complex market; firstly by its diversity, as Islamic art productions span across fourteen centuries, every media known to men, and more than half the world. Secondly, by the inherent difficulties and uncertainties that arise from dealing with this large variety of objects. Provenance is a large debate, particularly surrounding archaeological artefacts, but auctions are also impacted by legal restrictions on trade, such as the embargo on Iran, and by political or economic crisis such as the one in Turkey.

It is also a demanding market, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Demand is high for never seen before, exclusive pieces that are going to excite buyers, and auction houses have to continuously search for new. The Islamic art community is also full of erudite people who will question attributions and dating, including myself, though I am not as erudite as some! This search for previously unseen and extraordinary objects creates a lot of debates and controversies that have a direct impact on auction results.

However, for all these reasons, the Islamic art market is also very exciting, both intellectually and in terms of financial investment.

What about Provenance, how important is this in the Islamic art market?

The question of objects' provenance, meaning where they come from and how they arrived on the present market, has become prominent in the past few years, and for good reasons. Provenance research has always been part of the due diligence process of every auction house, but the wars and instability in the Middle-East for the past 20 years have put provenance research in the centre of a large debate regarding the protection of cultural heritage.

The Iraq war, started in 2003, and the Syrian war 7 years later caused an influx of imports in the West of archaeological artefacts either without provenance, or with fake ones, most likely forged in Turkey and Lebanon. Big auction houses had to react quickly against this influx in illegal trade, but not fast enough, as demonstrated by the Hobby-Lobby scandal, in which Christie’s sold cuneiform tablets looted in Iraq and is now engaged in a legal battle against the buyer[1].

Of course, not every object coming out of Syria and Iraq was looted, but auction houses need to be crystal clear on the provenance of the artefacts they sold, which is still not always the case, as they’re stuck between protecting the identity of their clients and being compliant with international legal standards that are putting more and more limitations on art trade.

There is also increasing scrutiny from the academic world on provenance of all types of Islamic objects, relayed on social media and in generalist publications. Christie’s sold a 15th century Timurid Qur’an on Chinese paper a few years ago and never mentioned its provenance in the catalogue, despite the manuscript being extraordinary and most likely produced in a royal context. It was a missed opportunity for Christie’s to improve the transparency of their trading practices, and it was not received well by the academic world.

The increasing effort on provenance documentation is a good thing, and it will hopefully lead to a more open and transparent market, but it also results in a difficult balancing act for auction houses and merchants that are required to offer never seen before objects, however with a documented and clear provenance. So far, it has proven to be possible, but increasingly difficult.

Can you tell us more about the protection of Cultural Objects and Art Market Practices?

The art market has always played a pivotal role in the protection of cultural objects and heritage but this is even more the case today for Islamic arts, which is why the current debate on provenance is so important.

In general, the question of protection of cultural heritage and the art market is so complex, because it touches international laws and conventions, but also trade and collection ethics, which is hard to quantify, and even emotions and public opinion, which should have little place in legal disputes but is so prominent. We are seeing it today with restitutions of looted artefacts during colonial times or by the Nazi, that encompass complex legal cases based on international conventions such as La Hague 1954 and UNIDROIT 1996, but also a strong support from the public for restitutions to previous historical owners.

To illustrate this complexity in regards to Islamic arts, I always give the example of architectural ceramics. The art market is full of ceramic tiles from Iznik (Turkey), Multan (Pakistan), Damas (Syria) and others. Some of these tiles are presented without provenance, which means we do not know how they arrived in private hands. Damascus tiles, for instance, might have been torn from a building in 2012 and illegally transited to Europe, which raises legal issues. However, these same tiles might have been removed in the 19th century and sold to a collector like the American Lockwood de Forest, who offered large sums of money for Damascus tiles. Some tiles from his collection were sold at Christie’s a few years ago, which poses no legal issues, but raises ethical questions about past collecting and trade practices that ultimately come down to individual sensibilities and public opinion.

You are a frequent at London Islamic weeks, what are they and how often do they take place?

London Islamic weeks, organized twice a year, usually around April and October, are vibrant moments for the Islamic art market. London auction houses with an Islamic art department hold their auction during these weeks, and of course London galleries are also presenting their selection, so all the actors of the Islamic art market are usually gathered. Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams offer the most prestigious selections, followed by Chiswick, Rosebery’s and Dreweatts (currently on hold), that have more affordable objects.

It is a buzzing moment and contrary to what people think, it is open to all, not just experts and merchants. If people have the opportunity to be in London during the Islamic week, they can go to the presale exhibitions, and even attend the live auctions.

Can you tell us about one of the most memorable Islamic artefacts you have encountered on the art market?

In 2019, I had the privilege to work on a page of the Royal Padshanama, sold by Anne-Sophie Joncoux-Pilorget at Millon et Associes. The page bears a painting from the illustrated reign chronicles of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, produced in 1630, which was later mounted in the so-called St Petersburg album, produced in Iran between 1735 and 1759 together with a Persian calligraphy from the 16th century, and wonderful golden margins. It is a fascinating artefact that really epitomizes the intricacies and the delicacy of Islamic productions. It is also one of the rare examples of objects with a clear provenance and an almost direct link to its context of production, so being able to study it really gave a sense of historicity that can be difficult to grasp when just seeing beautiful pieces in an exhibition. I am very grateful for this experience and hope more like this one will come!

What advice would you give to anyone looking to start collecting Islamic art. How do they access information about auctions?

The best advice to anyone looking into buying Islamic arts came from Anne-Sophie Joncoux-Pilorget, head of Oriental art at Millon et Associes in Paris, on the second episode of the ART Informant: “Buy what you like. Do not worry about financial trends, just buy something you will enjoy seeing in your home”.

I think following her advice is the best way to start collecting Islamic art, and the field is so diverse that everybody can find something they’ll love. Islamic art can also be a great financial investment, but people should not be expecting a rapid return on their investment, as trends come and go. Some types of objects could be considered as “safe bets”, meaning their value tends to remain stable and with little variations, but there is a part of chance in every auction.

For anybody wanting to start collecting Islamic arts, the best thing is to open auction catalogs and see what is there. March 2022 Islamic week catalogs will be freely accessible online in a few weeks, so they can start there. You can also speak to experts and people like me who will happily guide you through the current market. One thing that needs to be said to any new collector is that buying art - any type of art - needs to be carefully planned and budgeted. Prices can get high and bidding in an auction can trigger a dangerous sense of commitment so it is important to set a limit and stick to it, even if we end up disappointed. Here again, it is better to get in touch with auction houses, galleries, or myself!

Can you tell us more about the ART Informant Podcast which you host. What is the intention behind it?

I created this podcast at the end of 2021 as a way to promote Islamic arts initiatives and connect the actors of the field. In the episodes, I welcome experts, merchants, scholars, curators, artists, and everybody involved in arts and history from the Islamic lands. The episodes are published every other Monday on all audio platforms such as Spotify, Amazon music, Apple music and Google podcast, as well as on art-informant.com. It is completely free and accessible to all, with or without paid subscriptions to platforms.

The idea was to introduce a new medium, easy to access and to digest. Content dedicated to Islamic arts already exists on the internet, but it is either too specialized, aimed at academics, or on the contrary aimed at an audience that is new to the topic. I wanted to offer a satisfying in-between, but mainly I wanted to put actors at the center of their field, give them a platform to share their passion and their mission. Podcasts are a great way to do this in a transparent and informal fashion, but the medium is also a good support to talk about the news with people making the news.

What content can listeners expect from the episodes?

In the episodes, listeners can get insights, stories and a behind the scenes from some of the world's best Islamic art specialists.

They can learn about Islamic art history, of course, but also about the conservation of cultural heritage, the creation of exhibitions, the publication of books, how to prepare an auction, and much more. The content is diverse and through the theme of Islamic arts appears the vast world of art, so everybody with an interest in it can find something for them.

Can you share your upcoming projects?

This year is going to be focused on two main projects:

First, develop the ART Informant further and expand on the concept with additional formats and contents. I won’t say more on this now, as I’m still in the planning stage, but more to come this year.

Secondly, I want to publish my doctoral thesis as a book. This is a personal project that has been on the back burner since 2015, and I recently took the decision to carry it out in a more structured fashion. I wrote my thesis in French, so I want to rewrite it in English and review its content, as my approach and my views have evolved over the years. I will start writing in May and will submit to a scientific editor by the end of the year.

In addition to these two projects, I will continue offering my expertise to the art market, institutions, and collectors. This is something that I love doing and that allows me to meet passionate people and see beautiful things, so I definitely want to broaden that activity.

What does the future of Islamic art and culture look like to you and what influence will the art market have on its development?

We are living through critical times, in which cultures and cultural heritages are being threatened from many sides, but we also see a lot of artists, scholars, curators, educators and experts coming together with the mission to protect and highlight these heritages. The artistic scene is truly booming, it is a wonder to witness so much creation, some based on ancient techniques almost completely forgotten, some completely new and using modern technologies. This makes me very optimistic for the future of Islamic arts and cultures that continue to create harmony between tradition and modernity.

Here again the art market will play a pivotal role in promoting new creations and Islamic arts in general, as well in finding forgotten beauties to offer to the public. Auction houses will most likely intensify their actions against illegal trade if they want to preserve their reputation, which will hopefully result in more transparency and a better collaboration with academia. Time will tell!

For more information check out www.isabelle-imbert.com

Twitter: @art_informant

Instagram: @isabelle_imbert_phd and @art-Informant

The views of the artists, authors and writers who contribute to Bayt Al Fann do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Bayt Al Fann, its owners, employees and affiliates.

The interview with Isabelle Imbert about Islamic art is very insightful. The issue of market transparency and the origin of objects in 2026 is critical. It is important to maintain purity not only in history but also in physical space. I was looking for a solution for removing an old archive and found https://affordablewastemanagement.co.uk/, which also helps to keep everything in order. An honest approach is the key to success in any endeavor.

Hey everyone, a friend sent me this site during a late-night chat about online games in Bangladesh. I opened https://jtwin-bd.com/ while scrolling through our conversation and was impressed with how smooth the login process and navigation felt. The live tables ran well, and switching between games didn’t confuse me at all. I spent a surprising amount of time exploring and left feeling like it was easy and enjoyable to use.

I appreciate you sharing such thoughtful content. it’s an absolute must-read ! Real Pune Service {} Chennai Service {} High-Prole Chennai Service {} Trusted Hinjewadi Service {] Independent Wakad Service {} Real Baner Service {} Hotel Escorts In Pune {} Pimple Saudagar Service {} Bavdhan Service {} Kothrud Service {} Magarpatta Service {} Lonavala 410401 (+) Ravet 410121 (+) Wakad 411057 (+) Hinjewadi 411057 (+) Baner 411045 (+) Aundh 411007 (+) Pimple Saudagar 411021 (+) Shivaji Nagar 411027 (+) Kalyani Nagar 411014 (+) Viman Nagar 411014 (+) Magarpatta City 411013 (+) Pimpri Chinchwad 411033

شيخ روحاني

جلب الحبيب

الحصول على باك لينك قوى لموقعك من خلال تبادل اعلانى نصى

معنا عبر004917637777797 الواتس اب

شيخ روحاني

جلب الحبيب

Berlinintim

Berlin Intim

https://www.eljnoub.com/

https://hurenberlin.com/

سكس العرب

شيخ روحاني لجلب الحبيب

شيخ روحاني

رقم شيخ روحاني

رقم شيخ روحاني

شيخ روحاني في برلين

رقم شيخ روحاني 00491634511222

الشيخ الروحاني

شيخ روحاني سعودي

شيخ روحاني لجلب الحبيب

Berlinintim

bestbacklinks

backlinkservices

buybacklink

Berlinintim

Escort Berlin

شيخ روحاني

معالج روحاني

الشيخ الروحاني

الشيخ الروحاني

جلب الحبيب العنيد

جلب الحبيب بسرعة

شيخ روحاني الاردن

شيخ روحاني عماني

شيخ روحاني سعودي

شيخ روحاني مضمون

شيخ روحاني مضمون

معالج روحاني سعودي

شيخ روحاني مغربي

شيخ روحاني في قطر

شيخ روحاني لجلب الحبيب

شيخ روحاتي في السعودية

شيخ روحاني في البحرين

شيخ روحاني في…

Best IPTV Enjoy premium IPTV channels in ultra-clear 4K quality, bringing you everything from global news to entertainment in one place. Best IPTV